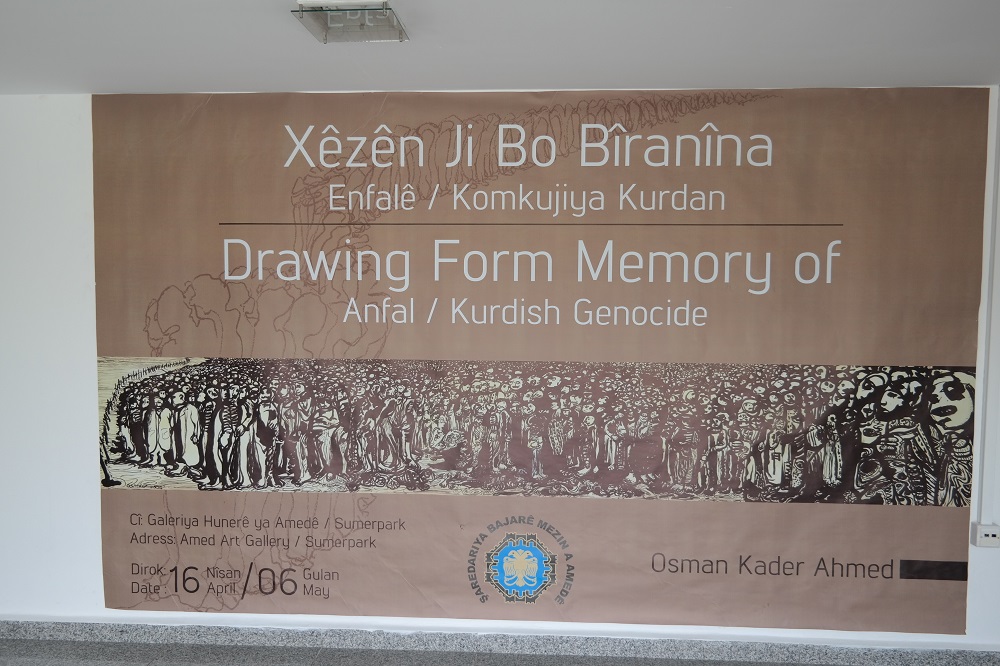

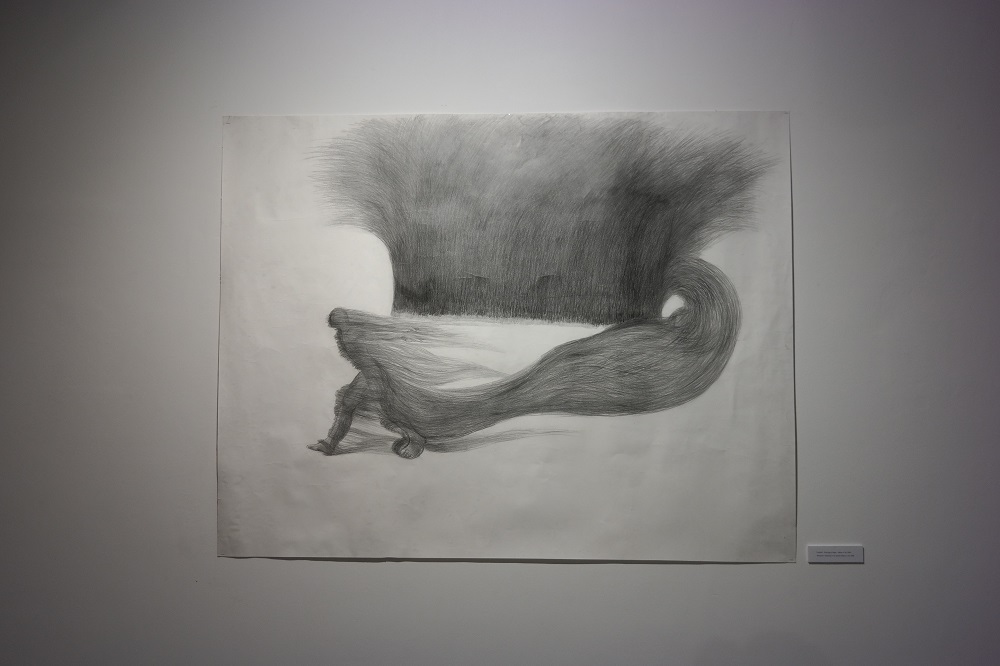

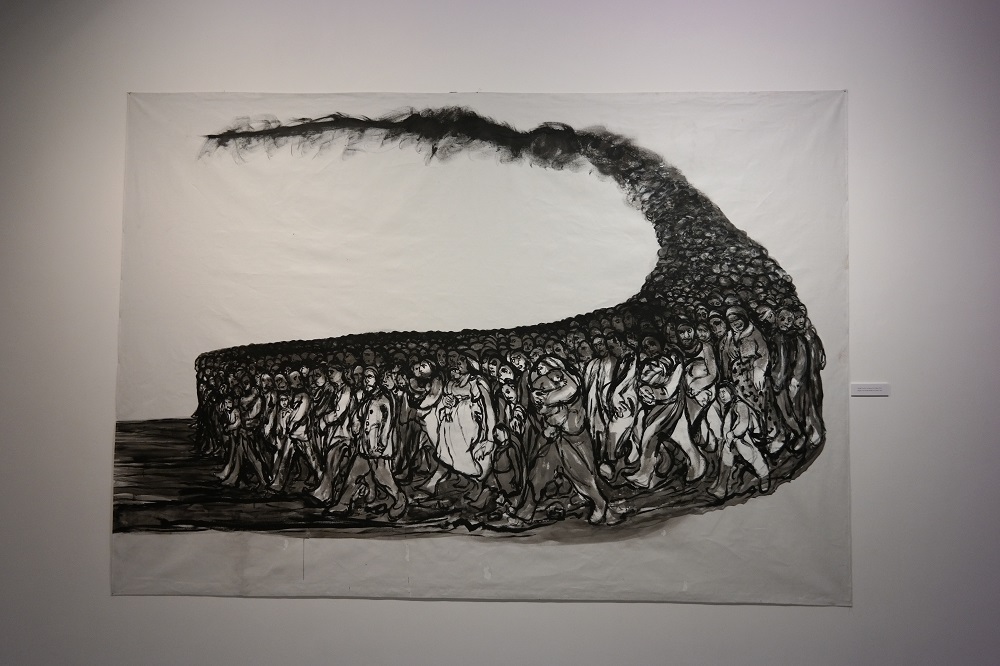

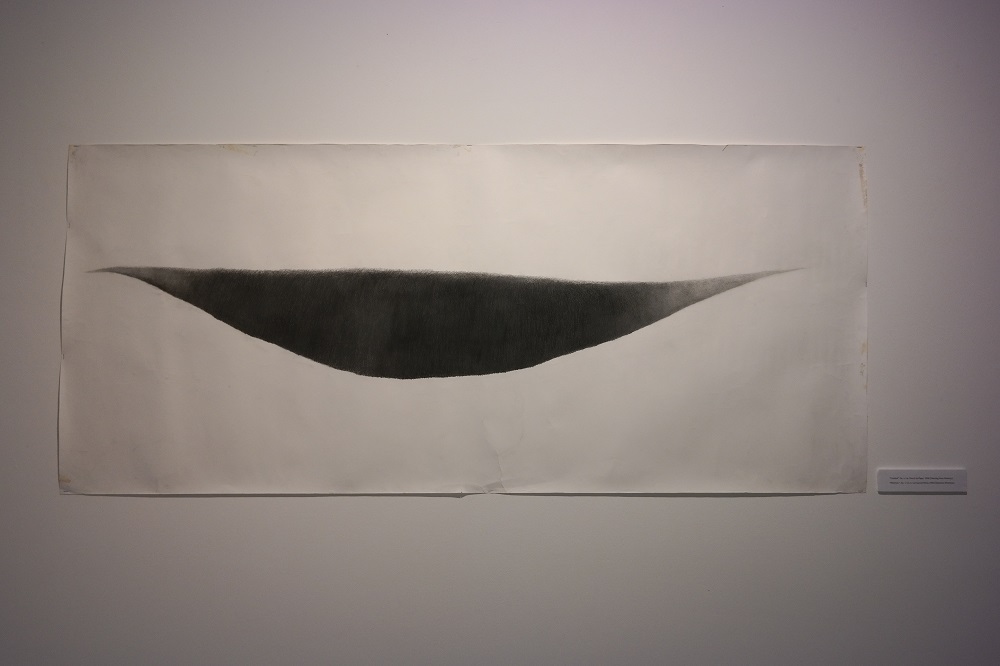

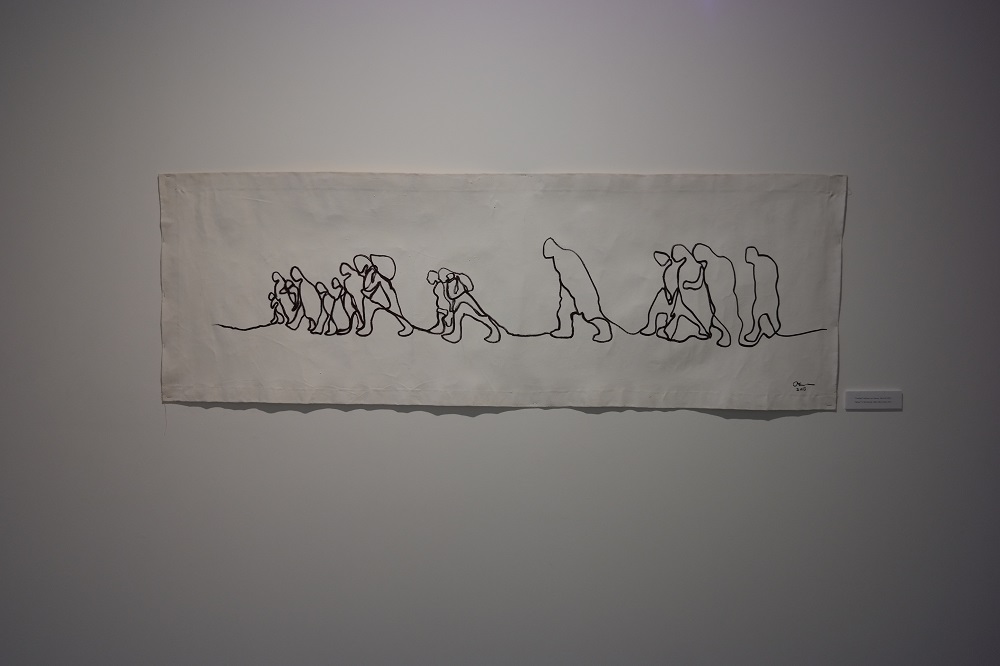

Drawing Form Memory of Anfal / Kurdish Genocide – Osman Kader Ahmed | 2015

Where Osman Ahmad’d drawings come from?

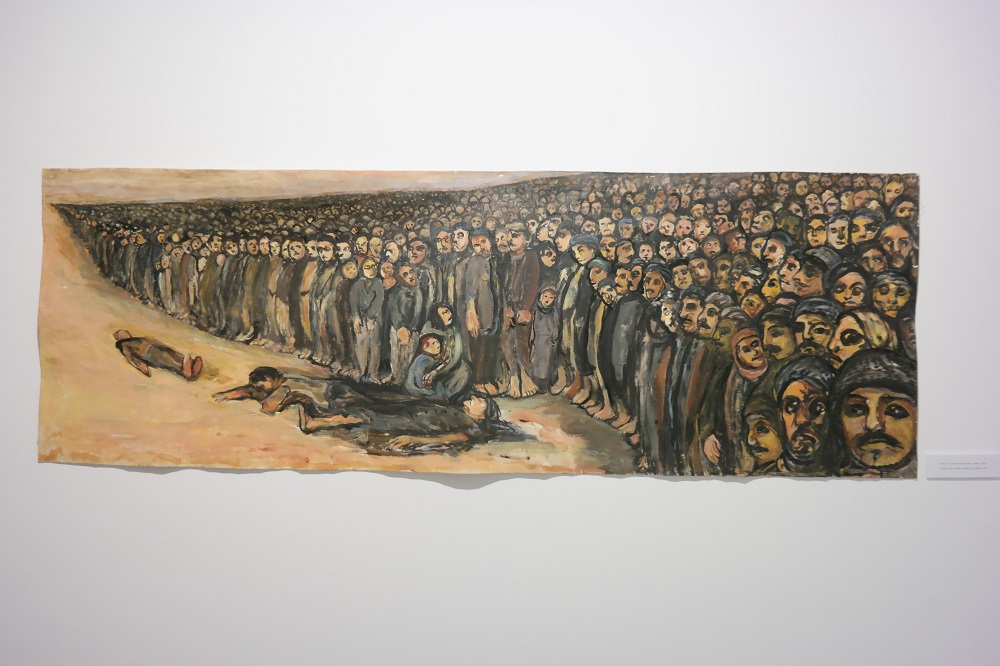

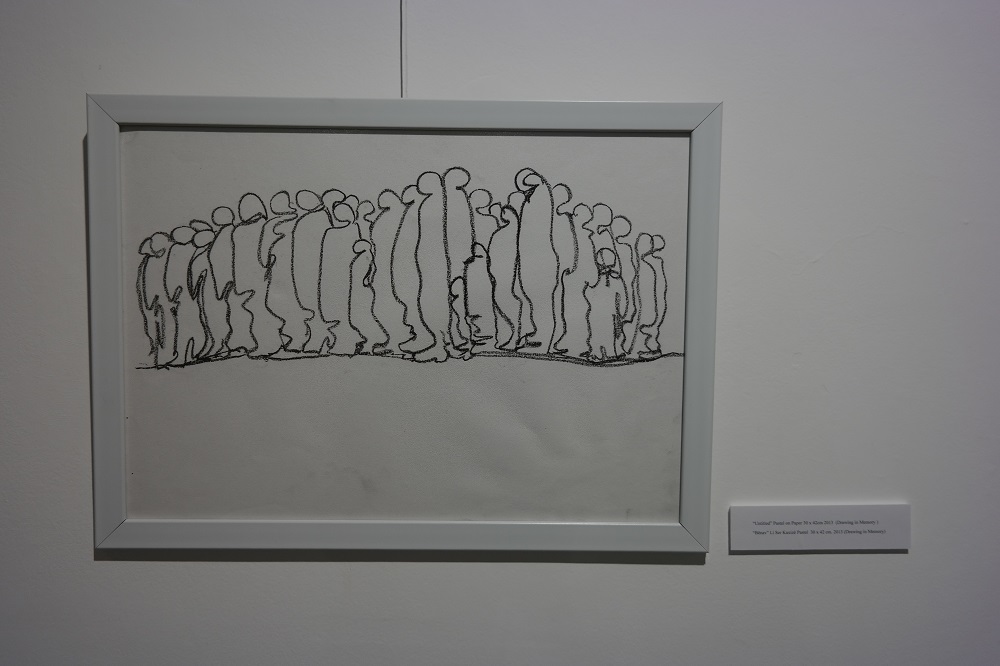

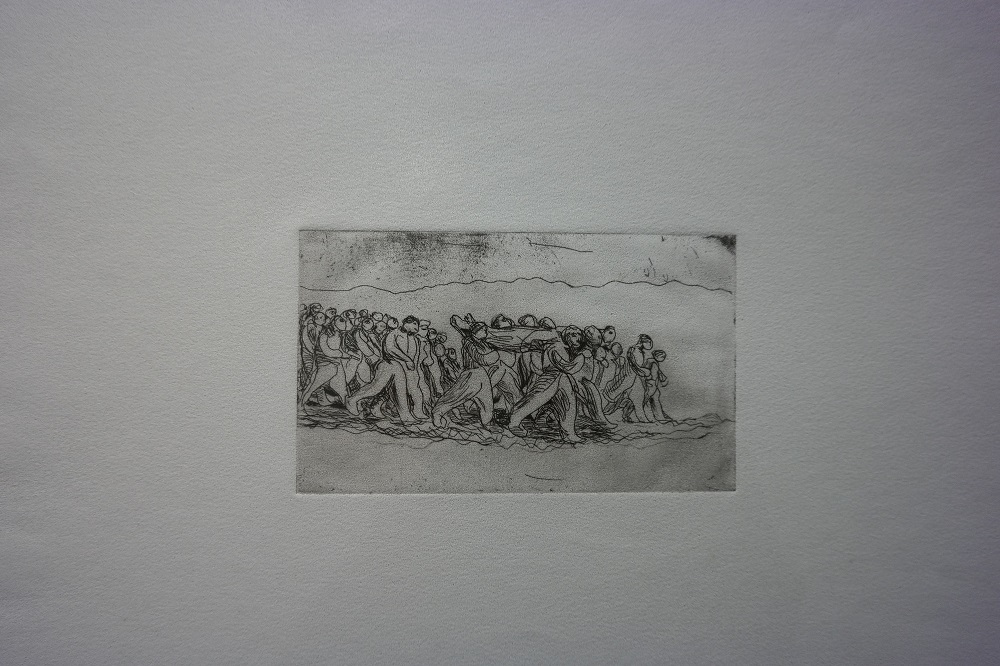

Most of Ahmad’s drawings come from his memory and his experience, as an eye witness, as a child, and throughout the years of political and cultural repression culminating in the horrendous event in 1988 that left a profound effect on his life. By presenting a body of works, he attempts not only to record the genocide (the Anfal) and a world of flashbacks and dreams, but simultaneously to explore and to a large extent, make known his feelings through the creative process. He thinks that no artist can create disturbing works without having felt or shared the suffering of others. He uses his drawings as a diary, recording painful narratives that through time and space and sequence by sequence, echo in his mind. He is surrounded by his drawings; but events are always in his imagination: real shadows of the figures in the drawings are part of his daily thoughts. The act of drawing gives him satisfaction and has a meditative effect; He feels his line is a living memory, a dominant figure, or rather a hero in the vast space of a desert or a hillside of high mountains in his native land – a vast space within which so often is present an imprint of a hand, a finger or part of a body in an unfinished sketch manner, entering into the ground or appearing, or fully emerging or disappearing. Bodies of the young being separated from the old, men from women, children from their parents whose belongings possessions are by no choice of their own left behind, which suddenly have no value anymore as they have been denied and forced to leave, and more often than not are destroyed in front of them. Although the last century was nothing short of a ‘century of death’ from the mass annihilations in South America to South Asia, Europe, Russia, Africa to the infamous ethnic cleansings – as an eye witness, in the company of a small group of freedom fighters sheltering among high mountains, it was very hard for him to believe that he was ‘witnessing’ a ‘massacre’ happening in front of them and not being able to do anything. It was a living nightmare. Few of them survived the genocide to witness further widespread mass executions of thousands of men and women and children, many of whom were buried alive, from women in labour to young men and children, and the necessary mass graves one after another to hide the evidence. These events as well as his personal circumstances and other accounts have given him a continual source of often uncomfortable imagery but nevertheless a powerful reason for working. Ever since this experience, he has been traumatised by the events and his artworks have been totally dominated by this subject matter.