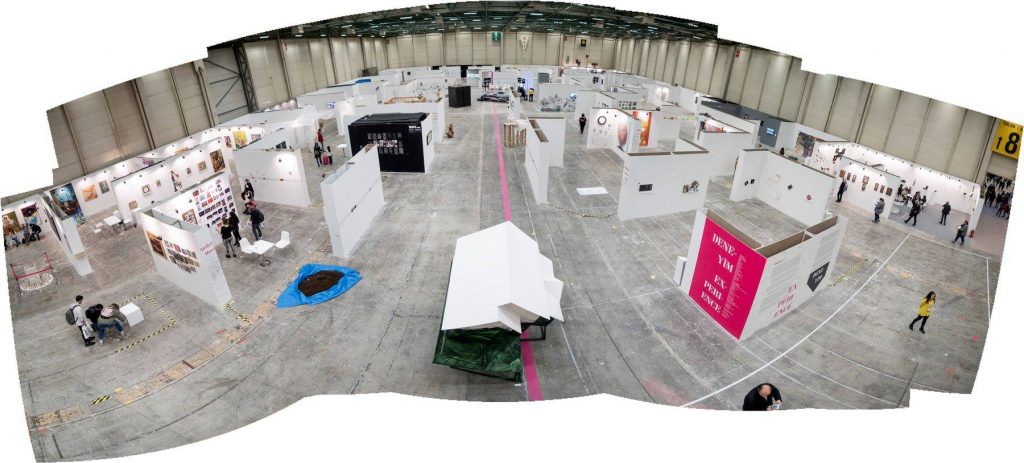

28th İstanbul Art Fair – Experience | ARTIST 2018

Coordinators: Ezgi Bakçay | Eda Yiğit | Barış Seyitvan | Irmak Züngür

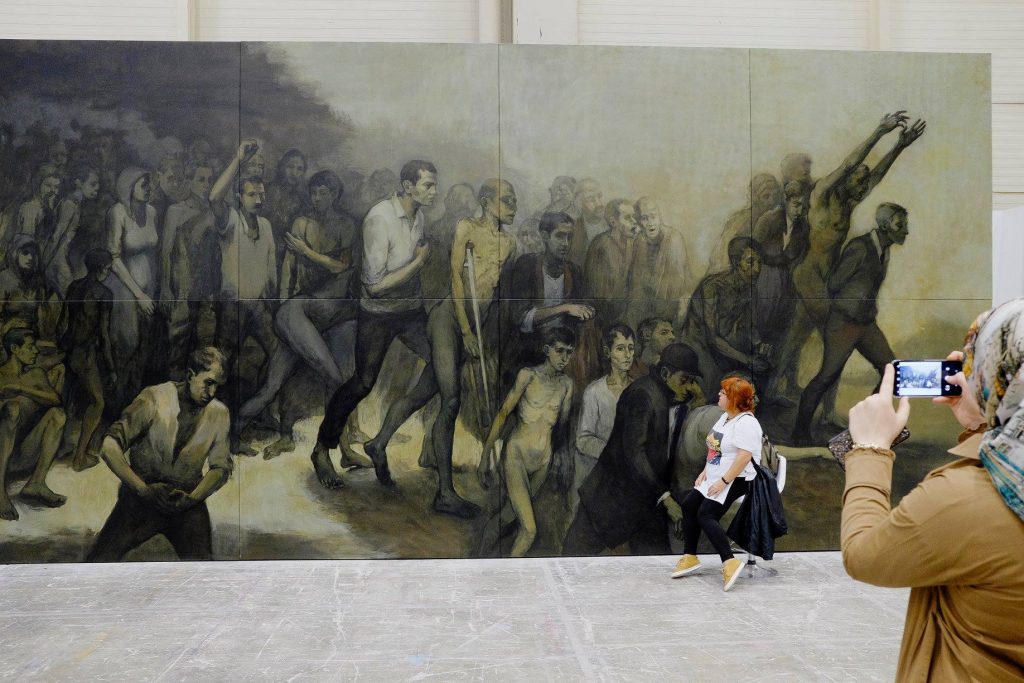

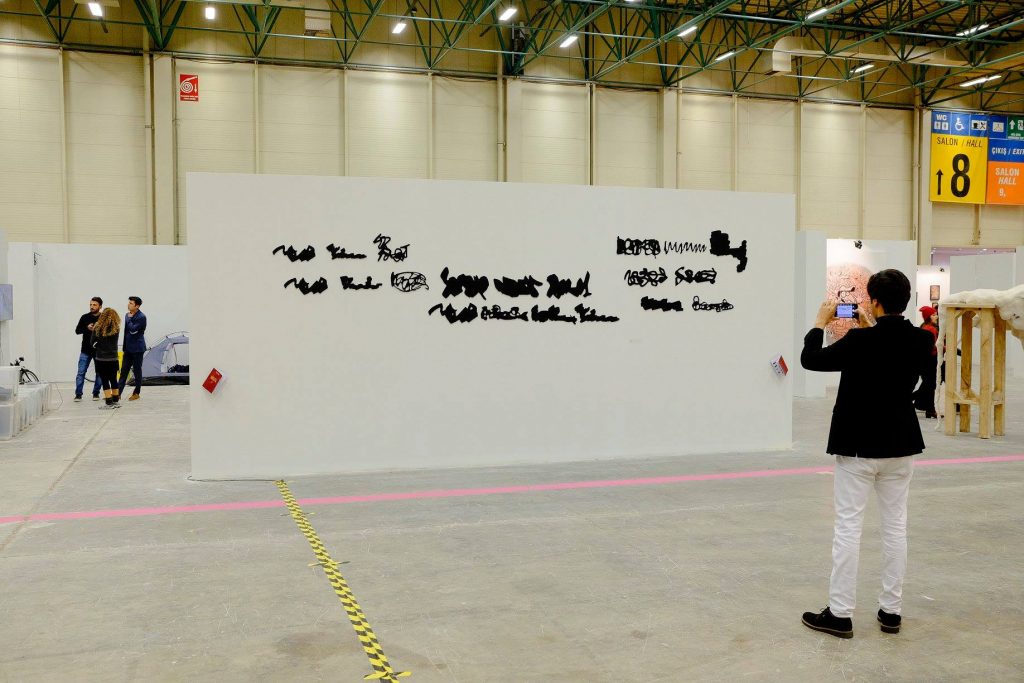

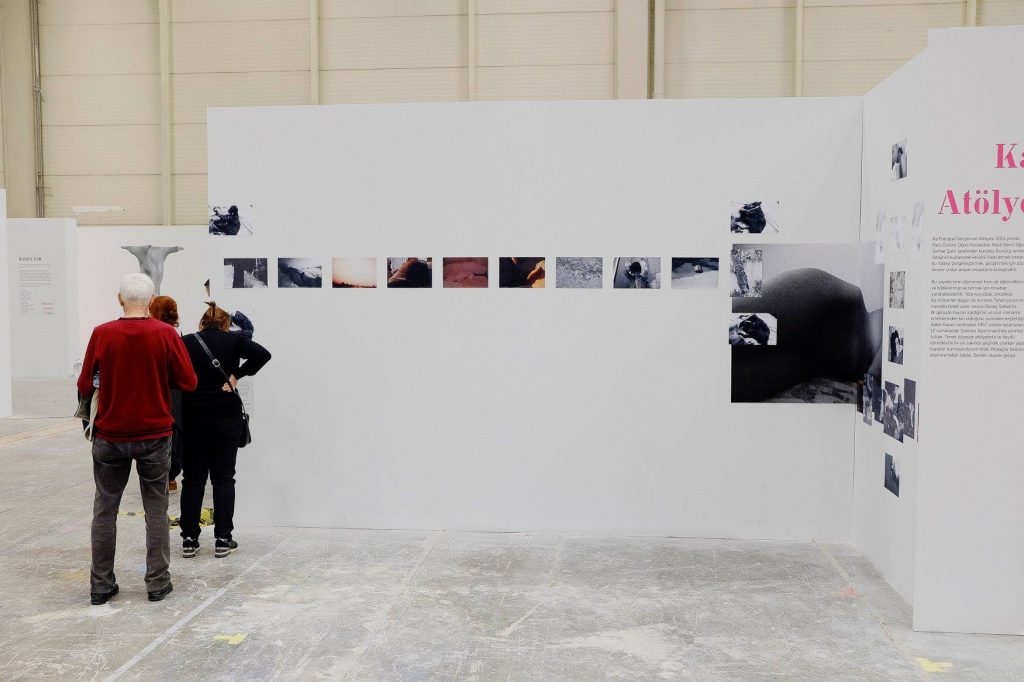

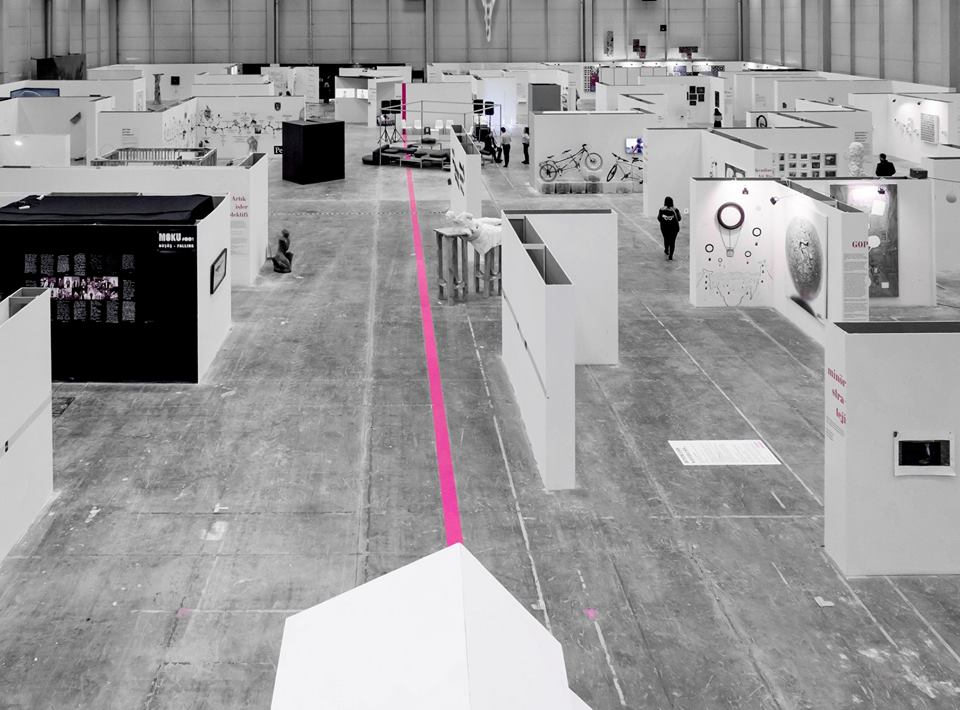

The 28thİstanbul Art Fair, to be held between November 10 and 18, deals with an elusive concept: Experience. The event hopes to be a profound, challenging and provocative praxis with artist initiatives from Turkey and the world.

Who first thought of treating experience as a separate category? Wouldn’t what we call experience include more or less everything that has ever been lived? How do we tell apart an exceptional experience from an ordinary one? More importantly, when and why did we need such a distinction? We have been through times when experience was King. Now, we question it amidst the disappointment of its unfulfilled promises. Experience can now be bought and sold; accumulated. The connection between experience and reality is replaced by its market value, and esthetic experience is the first to go. Like Oscar Wilde suggested, experience may be the name one gives to one’s mistakes. But what if one continues making the same mistakes despite thousands of years of life experience? To experiment: maybe this is where hope prevails in the experience. The human, as a creature capable of amazement and delight, continues to be fascinated by the world and be convinced that all experience matters.

“Plato and Spinoza saw it as a realm of illusion, to be contrasted with the pure light of reason. Jacques Derrida deeply disliked the notion, suspecting it of dark metaphysical tendencies. For William Blake, (…) experience is a domain of false consciousness and fruitless desire. For Romantics like Keats, by contrast, it is the zone of sensuous immediacy in which truth is revealed. (…) For empiricists like Locke and Hume, experience is what informs us that our feet will still be there when we wake up in the morning.”[1]

Modern philosophy asked about the share of feelings in the human’s knowledge of the world, and determined the value of the notion of experience based on the answers. When philosophy turned its face to the senses, experience was elevated; it was embraced as the source of senses liberated from the yoke of a disembodied mind, of the knowledge promising to make humanity one. But as communication technology and industry passed a certain mark of development, the question about the value of experience gave way to a concern of losing experience in the modern, urban world.

“Walter Benjamin saw it as the stories which the old recount to the young, and its disintegration in modern times seemed to him one of the most grievous forms of human poverty. The warning that experience is fading from the modern world is sounded all the way from Heidegger to Adorno.”[2]

Having been witness and victim to world wars, humanity views the pure light of reason or the innocence of sensuous immediacy as specks on the horizon. Under exigent circumstances like these, art always comes to the rescue of experience. The cradle of contemporary art since the beginning has been the experiencing body. In the interwar period, avantgarde movements ensured that experience was no longer singular and private, and collectivized it, making it political. The moment they include art in the practice of everyday life, experience suddenly gains supernatural powers. In fact, avantgarde has assumed the romantic promise of esthetics: Art is the only instrument that can reconcile the needs of the mind and body, the individual and the society. A society composed of free individuals can only become an esthetic community. This will bathe modern social life, the dungeons of commodity fetishism and sensory estrangement in the light of esthetic experience. But things don’t go as planned. Everything in the world arrives at the lowest common denominator of poverty and banality precisely at the speed of capital circulation, while the extraordinary has its shelter looted. Years when art was regarded as the means of liberating performance, everyday life, ordinary objects or immediate experience have been followed by a time when experience become commoditized by the same means.

Who owns experience nowadays? Thinkers of art and politics argue that experience as a category is facing peril in the neoliberal imagining, instigated by the discourse of the death of the subject, while the “experience market” continues to expand. As subjectivity, publicity, communality, reality and freedom lose their attraction, experience becomes irresistible. Experience is the mantra of 21st century businesses: Experience economics, experience management, experience design, brand design are all catchphrases in the white-collar world. Culture industries are also madly in love with experience. The lackluster everyday life in the age of giving up and letting go is rife with experiences that will “change your life.” It’s possible that the product has a price that is too steep, but it earns you symbolic capital far more than most items you could own. As experience becomes an object of desire, an instrument of investment, or even private property that is detached from the generality of life, life itself becomes the break between two experiences, an ascetic interlude that one must abide. This is a transition: from a person who dreams of the holistic transformation of life through experiences, to a person who desires to possess yet another experience. Art, gastronomy, tourism, activism, mysticism… Experience is the great equalized of all situations that temporarily stimulate our senses in different ways. Sensous promises that have bestowed special powers on commodities since the beginning are now on the market, wrought free of their corresponding objects. Like Eagleton says, “The word experience, perhaps intended to mean something with exceptional value, has turned into a calque that levels all.”{3}

Contemporary art is also built on experience. The latticework of relationships between artwork, the place of art, the artist and the audience cannot be interpreted without resorting to the notion of experience. However, experience has been relocated from the utopian temporality of the avantgarde to the “eternal present” of actuality. The experiences lived by the artist when making works of art, and the experiences of the viewers are as rich and diverse as they are intermittent and fragmented. The rhythm and speed of experience is set by social media. Under the current institutional autonomy of art, an esthetic experience that is supposed to overstep boundaries and awaken the audience in a sensory reveille may easily find a place for itself in the performance culture. Putting the virtual world at work, it can effortlessly reconstruct an experience of space travel, wild game hunting, natural disaster, terrorist attack or revolution for its audience. Ultimately, the question is whether a person will be able to breathe in the critical gap that forms between the experience and the real world.

In the industrial society, labor processes had ceased to be an experience for people; the post-industrial labor market prefers an inexperienced workforce. On the other hand, artificial intelligence hoards experiences within the stores of global companies. Scientific and technological breakthroughs point at a new, post-experience age, an age called post-humanity. Ever since becoming a commodity that can be sold and bought, even the most essential experiences promise no more subjectivity than the “perfect customer.” Culture industries offer contemporary art experiences as premium products. Amidst this confusion, can art still be the space of experience for non-alienated labor, or an ethical and political bearer of value as a means of fascinating the world once again? Does such an attempt at compensation deserve to be defended despite everything? Does the category of experience still possess a potential for liberation in art or life?

Eagleton sums it up: “We would have had an easy time if experiences openly showed their intrinsic politics, but that is not the case. First we need to interpret experiences, and as Perry Anderson observes, extreme political opposites may be derived from one and the same experience. It is true that experience is mostly a conservative notion: custom, habit, tradition and common sense are related to experience, yet even radicals have their own customs and geneological tables. In any case, it is an egalitarian attitude to consider experience the basis of all, since unlike a title or an Oxford degree, everyone has an experience. (…) From this point of view, experience is both essential and extremely unreliable.”

The 28th İstanbul Art Fair deals with the difficult and

prolific notion of “Experience.” The Fair invites all participants to

discuss the concept of experience from the perspective of esthetics, ethics,

labor, science, science-fiction, technology, history and popular culture. The

project section of the event houses artist initiatives and the collective

subjects of the cultural sphere.

Excerpt from Terry Eagleton’s “Lend me a Fiver”, published in London Review of Books on June 23, 2005.